|

Rolling

Forward: How Wheelchair Basketball’s

History, Progression, and Dynamic Influence

Have Impacted Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation:

Physically and Psychologically

by Monique

Jackson; msjakson@ufl.edu,

Undergraduate Student, University of

Florida, Gainesville, FL

Background Information

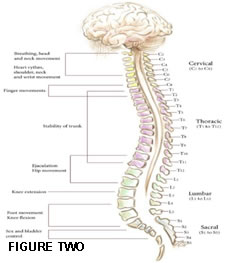

The spinal cord is essential to life

due to its three principle functions:

1) sensory and motor innervation of

the entire body inferior to the head,

2) two-way communication between the

body and the brain, and 3) a major center

for reflexes. (11) Any disruption to

this pathway due to some type of trauma,

either directly to the spinal cord or

indirectly, caused by damage or swelling

of the surrounding tissue that puts

debilitating pressure on the spinal

cord (Figure 1), will result in a less

than optimal quality of life. Both instances

can be easily avoided, but also experienced

with the same ease. This is due to the

anatomy of the spinal cord, which in

a living individual has the consistency

of a ripe banana, causing it to be easily

bruised, torn, or crushed with any significant

damage causing permanent injury, known

as paralysis;

and resulting in permanent change in

normal motor, sensory, or autonomic

function. The body parts that are affected

are those below the lesion, and depend

on the type of lesion: either complete

or incomplete (Figure 2). According

to Stopka and Torodovich, “A ‘complete’

injury means that all motor and sensory

function from the lesion down has ceased.

An ‘incomplete’ injury implies

that some motor and/or sensory function

remains intact” (8, p17).

|

|

History of Wheelchair Basketball

The history of human experience with

spinal cord injuries

(SCI) has been a complex and dynamic

one; enshrouded in a cloak of doubt

of the future, depression of the present,

and anguish of missing one’s past.

Yet, the tales of time have had a parallel

of these experiences with ways to combat

and counteract the transformation that

they bring upon people. Many of these

tales find their biggest moments to

have occurred as a result of World War

II (WWII), in which great numbers of

young men enlisted in the military suffered

traumatic injuries that resulted in

paralysis. These soldiers needed ways

to combat the prevailing thought of

the time that “nothing can be

done for these young men” to fight

back toward leading a fulfilling life

in every aspect of society. Wheelchair

basketball became an indispensable

rehabilitation tool affecting both physical

and psychological troubles for those

with SCI during the war and well into

the future.

Sir Ludwig Guttmann’s

Impact

During these times, complications that

followed SCI, such as malfunctions of

the kidneys and bladder, as well as

infected bed sores, were thought to

be ordinary hardships along the inevitable

road to death. However, there was one

courageous and hardworking doctor who

worked tirelessly to combat “this

defeatist attitude” (3) and his

name was Sir

Ludwig Guttmann. What gave Dr. Guttmann

the passion to pursue routes that could

combat the defeatist attitude was his

time serving as an orderly in WWII,

in which he saw a patient, a well built

and strong looking man, brought in and

placed at the end of the ward, and surrounded

by screens in an attempt to make his

dying days, weeks, or months private

and more bearable. This prompted in

Dr. Guttmann the need to overcome the

defeatist attitude toward SCI, and formed

his personal philosophy “that

these complications could not only be

controlled but altogether avoided”

(3).

Later on during WWII Dr. Guttmann,

who quickly rose to the top of his field

of neurology and became a renowned brain

surgeon, fled from Nazi Germany to Great

Britain to work at The Spinal Rehabilitation

Hospital in Stoke, Mandeville, where

he developed wheelchair netball to aid

in the rehabilitation of veterans. There

Dr. Guttmann became conscious of the

fact that not only did those with paralysis

face physical problems, but also mental

and social psychological problems; particularly

in the veterans he worked with he noticed

societal withdrawal and depression.

This was another innovative thought

on his behalf that led him to form rehabilitative

programs that worked to not only help

prolong life, but also to fight the

psychological factors, and help to assimilate

the young men as useful and respectful

members of society.

Dr. Guttmann worked towards these goals

utilizing sports for he believed it

“would encourage them to make

the most of their remaining physical

capabilities, provide much-needed exercise

and restore mental equilibrium”

(3). From then on Dr. Guttmann enforced

mandatory participation in athletic

and physical activities while patients

with SCI were staying at the Stoke facility.

The program utilized therapeutic qualities

of physical activity that allowed veterans

to regain their coordination, strength,

and confidence to find available jobs,

and regain a self-fulfilling role in

society once more. Consequently, the

mandatory participation led to competition

amongst the patients and the hospital

staff, resulting in the first Stoke

Mandeville Games for the Paralyzed,

which was held on July 16, 1948, the

same day as the Olympics.

The rehabilitation to this sequence

of events is inherent, in that it made

the patients active and physically engage

their bodies. Yet, it must also be noted

the psychological benefit that the competition,

especially the Stoke Mandeville Games,

had on the patients who went from being

bed-ridden and possibly on their deathbed

to inclusion in “regular”

activities and games that showed them

their physical ability and potential.

It is apparent that not only did Dr.

Guttmann’s programs have a physical

benefit, but they also helped to rework

the psyche, as was acknowledged by one

patient in particular who was quoted

as having said: “We’re so

busy in this bloody place we haven’t

got time to be ill” (3).

National Wheelchair Basketball

Association

At approximately the same time Dr. Guttmann

was working to use sports and netball

as a therapeutic tool in Great Britain,

there was a similar movement in America.

Wheelchair activities and sports started

as a way for WWII veterans with paralysis

to become active once again. Initial

sports ranged from ping-pong to volleyball,

and finally to fast paced sports such

as touch football and basketball. Credit

for the creation of wheelchair basketball

is not clearly identified, but has been

generally shared between the California

and New England chapters of Paralyzed

Veterans of America (PVA). Both

agree that the game got its start circa

1946, and with popularity spread across

New England and the Midwest and then

onto Canada and across the pond to England

(1).

By 1948 there were six teams that operated

out of Veteran’s Administration

(VA) hospitals that participated in

the PVA tournament. The first “civilian”

team, or team not affiliated with a

VA hospital, was the Kansas City Wheelchair

Bulldozers, later called the Rolling

Pioneers. This was monumental, yet the

PVA tournament was still very exclusive,

open only to veterans with paraplegia

or SCI. Not surprisingly this exclusive

tournament eventually folded to the

more inclusive and tougher competition

of the National Wheelchair Basketball

Association (NWBA) in 1948. The inclusiveness

of the NWBA speaks volumes of how it

helped in the psychological development

of current participants, and the newcomers

who previously may not have had any

other way to engage in an activity that

disregarded the fact that they are wheelchair

bound or enabled them to be physically

active. The mission of the NWBA is:

“In our pursuit of excellence,

the National Wheelchair Basketball Association

provides qualified individuals with

physical disabilities the opportunity

to play, learn, and compete in the sport

of wheelchair basketball” (1).

Tim Nugent’s Impact

A principal organizer of the NWBA, and

a leader in the use of the sport as

a rehabilitation tool is Tim

Nugent, the former Director of Rehabilitation

at the University of Illinois (UI).

In 1949, along with a group of UI students,

Nugent formed the first NWBA tournament

in which six teams played. The tournament

resulted from an effort to provide Nugent’s

team, the Illinois

Gizz Kids, with outside competition.

Like Guttmann, Nugent saw the psychological

and social void from paralysis that

wheelchair basketball filled: “The

heart and skill shown by participants

in wheelchair basketball will soon remove

the apathy which has surrounded the

so-called physically handicapped, and

force people to see the whole scope

of life, what can and needs to be done.

It is my hope that wheelchair basketball

will remain a game of the boys who need

it and want it" (7).

The NWBA grew immensely while Nugent

served as its first Technical Director

& Commissioner, fulfilling his role

to organize and administer the affairs

of the association. Nugent continued

the game’s connection with the

military by working with the United

States Armed Forces to utilize military

airlifts "to provide transportation

for needy member teams that had no formal

sponsorship or other revenues to get

them to the annual national delegates

meeting and championship games”

(7). His ability and efforts in working

with the military also provided a home

for the association’s annual events

at military bases located around the

country. Nugent’s work ensured

an annual representative forum to guarantee

participants’ involvement in the

decision making process. As Technical

Director & Commissioner, Nugent

introduced legislation that would regulate

the types of disabilities that could

play against one another resulting in

the functional ability point system.

This allowed for even matched play,

preventing a team from stacking athletes

with less severe disabilities against

athletes with more severe disabilities.

According to the International Paralympic

Committee the point system is set: “Depending

on their functional abilities a point

value from 0.5 (most severely disabled)

to 4.5 is given to each player. Five

players out of 12 from each team are

on the court during playtime, and throughout

the game the total point value of each

team must not exceed 14 points”

(2). Wheelchair basketball’s ability

to bring inclusion to a group that was

often separated from society is due

to the game’s similarity of regulations

to that of the able-bodied version of

basketball. As aforementioned the association

grew under Nugent’s guidance and

a number of powerhouse teams and dynasties

emerged throughout the years. Due in

large part to the tireless efforts of

Tim Nugent, the NWBA is regarded as

the standard for all organizations for

persons with disabilities.

PROGRESSION OF THE GAME

International Play

Even with all of his endeavors in America,

Nugent played a major role in the international

sector as well by negotiating and formulating

plans with other sport leaders, such

as Dr. Guttmann, to bring wheelchair

sports to the international level. This

resulted in wheelchair basketball being

played in the 1st Paralympic Games in

Rome, Italy in 1960. Now internationally,

those living with paralysis were able

to train, be physically active on a

daily basis, have regular interaction,

and utilize every therapeutic aspect

the game had to offer. Presently a kingpin

in international competition is the

World Championship, formerly known as

the Gold Cup Tournament. This groundbreaking

competition was the first for international

sport to allow people with amputations

and other non-SCI athletes to compete.

Women’s Introduction

into the Game

According to NWBA historian Stan

Lebanowich, the women’s game

was ushered in by the birth of the University

of Illinois’ Ms. Kids (another

resource) during the 1970s, whose

program was built by the athletes playing

able-bodies athletes (1). The women’s

game followed the same trend the men’s

game did to grow from a few teams and

nations dominating game-play and championships

to the creation of the USA’s National

Women’s Wheelchair Basketball

League in 2000.

Rehabilitative Effects from

Wheelchair Basketball Participation

Wheelchair basketball is a sport, under

any definition of the word, and like

any other sport participation in this

one requires training, which effects

strength and conditioning, which in

turn effects rehabilitation. This was

and still is doctors’ number one

motive when it comes to encouraging

patients with SCI to be physically active

and participate in sports. There have

been great strides in studies and research

to produce knowledge and information

regarding the rehabilitative effects

of participation in wheelchair basketball

towards both the physical and psychological

realm.

Strength & Conditioning/Physical

As far as the physical aspect is concerned,

studies have shown that just because

athletes may be in a sedentary position

it does not mean they should not utilize

and incorporate strength and conditioning

training. Training should be used as

both a part of their continuous rehabilitation

and preparation for sporting events.

There is no exception to the fundamental

rule that functional stability must

be increased before minimal loads, such

as the push required to propel a wheelchair,

or plyometrics

are incorporated. Both of these must

be applied to all wheelchair athletes.

One must remember, however, to regard

different functioning capabilities by

tailoring programs to specific athletes.

Experts strongly recommend for individuals

with adapted needs to regularly engage

in weight training activities to prevent

debilitating sequelae.

An effective weight training program

should include the following seven integral

components: 1) number of repetitions

to be performed, 2) numbers of sets

to be performed, 3) workload, 4) time

interval between exercises, 5) workout

frequency, 6) exercises to be performed,

and 7) exercise sequence (9). Research

has concluded that an adaptive weight

training program for athletes with disabilities

should include the objectives of strength,

endurance, and flexibility. Furthermore,

general criteria for a weight training

program should follow these guidelines:

regarding strength, “identify

the individual’s maximum weight

for the specific exercise that can be

lifted ten times in a row. Then, the

strength program will consist of lifting

50% of maximum weight for ten repetitions,

75% of maximum weight for ten repetitions;”

make certain the athlete utilizes progressive-resistance

exercise and have them perform three

sets a day, three times a week; as for

endurance “identify the individual’s

weight for the specific exercise that

can be lifted 50 to 100 times in a row.

Then the endurance program will consist

of lifting the maximum weight possible

for 50 to 100 times in a row, without

pain, etc.;” and finally for flexibility

have the athlete move the joint through

full range of motion without experiencing

pain (9, p200).

As with any other athlete an initial

assessment should be done to determine

the physiological profile, and to test

the different aspects of muscular strength,

sport specific flexibility, endurance,

power, balance, posture, and aerobic/anaerobic

energy systems. According to Ramsbottom,

“Wheelchair athletes need a great

deal of neuromuscular and core training

to help with stability, posture, coordination,

reflexes, and the transfer of power

during movement. The goal of neuromuscular

and core training is to stimulate the

nervous and muscular systems to create

a stable foundation to move from. The

core, the center of gravity of the body

located around the navel, should be

this foundation. Due to the nature of

a wheelchair athlete's movement patterns,

special attention must be made to strengthening

the posterior musculature. These upper

back muscles ensure muscle balance between

the anterior and posterior sides of

the body. Proper muscle balance will

help to maintain efficient movement

and allow for maximum power production”

(5).

It is common knowledge of the effects

that weight training has on bone structure

by helping to increase the density of

the bone. Studies have shown that radial

bone density is higher in wheelchair

athletes compared to their sedentary

counterparts with paraplegia. In recent

years, sports for athletes with physical

disabilities are gaining popularity

in Japan for its value in maintaining

and improving remaining functional abilities

and increasing independence and motivation

for life (6) Table 1. “Exercise

has also been proven to increase serum

levels of bone formation markers in

humans. These data support our findings

in which BMD [body mass density] of

the legs, body trunk, and entire body

among wheelchair athletes who restarted

sports activity immediately after SCI

injury was observed to be higher than

those who restarted their sports later”

(7) (Table 1).

Another study investigated the acute

changes in the bicep tendon after a

high-intensity wheelchair propulsion

activity. One aspect of this study showed

that, with respect to the participant’s

playing time, there was a change in

tendon diameter that reflected a positive

correlation. To put this simply, those

who participated for greater time periods

experienced a larger change in tendon

diameter than those who participated

for a shorter time period (12) (Figure

3).

Psychological

The psychological benefits of wheelchair

basketball can be witnessed on a superficial

level that can be experienced through

interaction with individuals with SCI,

and from listening to their reflections.

Yet, there are only a few studies that

have delved deep into investigating

this realm, where research has shown

that individuals with disabilities that

participate in activities and remain

physically active exhibit better mood

states, less stress, and greater functional

capacity and strength as compared to

their less active counterparts (10).

One particular study shows that an “interpretation

of the quotes and data reported by Taub

et al. was that the participants [in

a qualitative interview] appeared to

develop a sense of competency and skill

that allowed them to demonstrate to

others they were not sick or diseased

and could function similar to others”

(10). Consequently, an interpretation

held by many in the field is that the

psychological rehabilitative effect

wheelchair basketball has is that it

gives participants a feeling of inclusion

when meeting new people and expanding

their social interactions, greater strength,

less restrictions in their environment,

and awareness of improved health and

self-perception. All of these things

are necessary to have a stable mind

and body.

Conclusion

Inarguably, wheelchair basketball has

become an indispensable rehabilitation

tool affecting both the physical and

psychological concerns for those with

SCI. This has been witnessed from its

initial utilization during World War

II to its ever changing effects in the

present that will unquestionably continue

into the future. Wheelchair basketball

began as a way for soldiers to combat

the war era thought of “nothing

can be done for these young men”

to fight back toward leading a fulfilling

life in every aspect of society, and

its work continues today with the same

occurrence due to the Wars in Iraq and

Afghanistan. Appreciation and gratitude

must be give to the men, women, and

doctors who paved the way for those

to roll across the court today. So much

is to be gained from this sport due

to its physical and psychological rehabilitative

factors of strength, coordination, endurance,

a sense of cohesion and bond among teammates,

and the most important-the feeling and

knowledge that disability does not equal

inability.

REFERENCES:

- Lebanowich S. History of Wheelchair

Basketball. National Wheelchair Basketball

Association Web Site. 2007. Available

at: http://www.nwba.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=13&Itemid=120.

Accessed April 13, 2009.

- Wheelchair Basketball. IPC, International

Paralympic Committee Web Site. 2009.

Available at: http://www.paralympic.org/release/Summer_Sports/Wheelchair_Basketball/.

Accessed April 14, 2009.

- Jan Godfrey & Marilee Weisman.

A History of Wheelchair Sports: Sir

Ludwig Guttmann. Available at: http://www.spitfirechallenge.ca/Sir%20Ludwig%20Guttmann%20early%20history.htm.

Accessed April 15, 2009.

- Sports Science Committee. IPC, International

Paralympic Committee Web Site. 2009.

Available at: http://www.paralympic.org/release/Main_Sections_Menu/IPC/Organization/Standing_Committees/Sports_Science_Committee/index.html.

Accessed April 15, 2009.

- Ramsbottom S. Strength and Conditioning

Principles for Wheelchair Athletes.

- Miyahara K, Wang D, Mori K, Takahashi

K, Miyatake N, Wang B, Takigawa T,

Takaki J, and Ogino K. Effects of

sports activity on bone mineral density

in wheelchair athletes. Journal of

Bone Mineral Metabolism. 2008; 26:101-106.

- Timothy J. Nugent. National Wheelchair

Basketball Association Hall of Fame.

Available at: http://www.nwbahof.org/TNugent.cfm.

Accessed April 15, 2009.

- Stopka C & Todorovich J. Application

of Principles and Concepts: Physical

Disabilities. In: Applied Special

Physical Education and Exercise Therapy.

Boston, MA: Pearson; 2008: 17.

- Stopka C & Todorovich J. Therapeutic

Weight Training. In: Applied Special

Physical Education and Exercise Therapy.

Boston, MA: Pearson; 2008: 199-201.

- Giacobbi Jr. PR, Stancil M, Hardin

B, and Bryant L. Physical Activity

and Quality of Life Experienced by

Highly Active Individuals With Physical

Disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity

Quarterly, 2008, 25, 189-207.

- Drongelen S, Boninger M, Impink

B, and Khalaf T. Ultrasound Imaging

of Acute Biceps Tendon Changes After

Wheelchair Sports. Archives of Physical

Medical Rehabilitation. 2007; 88:381-385.

|