|

CEREBRAL PALSY AND STRENGTH TRAINING:

BENEFICIAL OR NOT

by Lori

Ann Bruns; University of Florida,

Graduate Level Distance Education Student;

Owner of Curves Fitness Center

INTRODUCTION

Strength

training is a vital component of a fitness

program. Many people consider strength

training as something only athletes

partake in, but strength is something

necessary for life. Without strength,

moving, walking, talking, eating, or

even breathing would be impossible (Koscielny,

n.d.).

In the last

few decades more is becoming known about

the benefits of muscle strength and

endurance ("Strength

Training," 2006). Research

over past years has found that strength

development is a vital part of most

health and fitness programs (Kraemer,

2003). A study by Winett &

Carpinelli (2001) demonstrates that

strength training has enormous effects

on the musculoskeletal system, assists

with the maintenance of functional capabilities,

and has the ability to prevent osteoporosis,

sarcopenia,

pain of the lower back, and other disabilities.

Some

recent influential studies show that

resistance training may also play a

role in resting metabolic rate, body

fat, blood pressure, gastrointestinal

transit time, which are closely linked

with heart disease, cancer, and diabetes

(Winett &

Carpinelli). Studies by Ebben

& Jensen (1998);

Fleck (1998);

Freedson (2000)

established that a strength training

program can have both physiological

and psychological benefits, for both

men and women (as

cited by Harne & Bixby 2005),

but what about men and women who have

cerebral palsy? Some

recent influential studies show that

resistance training may also play a

role in resting metabolic rate, body

fat, blood pressure, gastrointestinal

transit time, which are closely linked

with heart disease, cancer, and diabetes

(Winett &

Carpinelli). Studies by Ebben

& Jensen (1998);

Fleck (1998);

Freedson (2000)

established that a strength training

program can have both physiological

and psychological benefits, for both

men and women (as

cited by Harne & Bixby 2005),

but what about men and women who have

cerebral palsy?

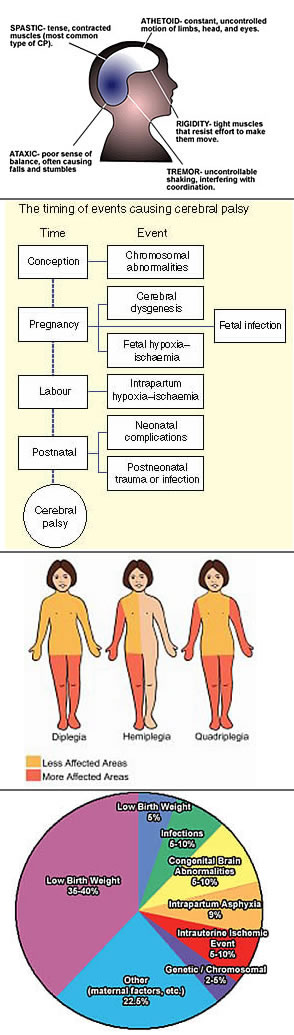

Cerebral

palsy (CP) is "a group of permanent

disabling symptoms resulting from damage

to the motor control areas of the brain…manifesting

itself in a loss or impairment of control

over voluntary musculature" (Winnick,

2005, p. 236). Cerebral palsy

is the most common cause of physical

disability in children with two out

of every 1,000 live births in the United

States (Lehman,

Garban, Scott, Tant, & White, 2008).

For years there has been hesitation

in the therapy world as to whether or

not strength testing and training should

be performed on people with cerebral

palsy, while some physical educators

and people in the medical field haven't

agreed with this perspective (Damiano,

Dodd, & Taylor, 2002).

Recently

a literature review was published refuting

the effectiveness of muscle strengthening

in children with cerebral palsy (Scainni,

Butler, Ada, & Teixeira-Salmela,

2009), going against previous

literature reviews by Darrah, Fran,

Chen, Nunweiler, & Watkins (1997),

Haney (1998),

Dodd, Taylor & Damiano et al. (2002),

and most currently, Verschuren, Ketelaar,

Takken, Helder, & Gorter (2007).

The reasons why strength training isn't

widely used by many physical therapists

are multifaceted (Damiano

et al.). The lack of strength

gains, increases in spasticity, and

inability to perform strength exercises

due to movement controlled by chained

reflexes were some of the reasons why

there was a believe that people with

cerebral palsy should not strength train

(Damiano et al.).

Due to such conflicting reviews it is

necessary to reexamine the topic of

whether or not strength training for

people with cerebral palsy is beneficial

or not.

CEREBRAL

PALSY AND MUSCLE STRENGTH, MOBILITY,

AND GAIT FUNCTION

"Our

bodies are miracles of adaptability,

capable of altering themselves in response

to loads placed upon them in such a

way that future, similar loads will

be less stressful. Likewise, they can

and will adapt to having no demands

placed upon them, becoming increasingly

weaker and less capable" (Strength

Training, 2006, para. 8). Bartlett

& Palisano (2002)

concluded that muscle strength, not

spasticity, is a main impairment that

plays a role in motor functioning in

children with cerebral palsy. Damiano

et al. (2002)

and Eagleton, Iams, McDoell, Morrison,

& Even (2004)

also agreed that muscle weakness significantly

decreases ambulation. Some therapists

are not eager to strength train people

with cerebral palsy due to the lack

of sufficient strength gains (Damiano

et al.) and no evidence of improvements

in activity (Scianni

et al., 2009).

A study done

by Scholtes et al. (2010)

evaluated functional progressive

resistance exercise strength training

on mobility and muscle strength in children

with cerebral palsy. Fifty-one children

with uni- and bilateral spastic cerebral

palsy were placed in either the intervention

group, which consisted of 12 weeks of

progressive circuit training, or the

control group, receiving usual care.

Muscle strength and mobility were all

measured before, during, directly after,

and six weeks after the training had

ended. The results showed a significant

change in muscle strength.

Knee extensor

strength increased by 12 percent and

hip abductor strength increased by 11

percent, while six-repetition leg-press

maximum increased by 14 percent. Despite

all the significant increases in strength,

no changes were observed in mobility.

The researchers stated that a probable

cause for not observing an increase

in mobility was because the improvements

in strength weren't enough in order

to improve mobility. Another suggestion

may have been that the number of each

individual muscle that increased in

strength was too limited (Scholtes

et al.).

To some extent

the results of the Scholtes et al. 2010

study coincide with the findings of

Damiano, Arnold, Steele, & Delp

(2010).

The aim of this study was to determine

if strength training could decrease

the extent of crouched, internally rotated

gait in children with cerebral palsy.

Eight children followed an eight-week

progressive resistance program. Measures

were taken before and after the program

in three-dimensional gait

analysis and isokinetic

testing. The results showed that the

left hip extensors had significant changes

in strength going from 10.7 ft-lb to

19.2 ft-lb (p=0.01), which is a 79.4%

change. The right hip extensors and

right and left knee extensors all increased

as well, but non-significantly. In terms

of gait

kinematics,

some but not all of the children improved

with hip and knee extension.

Stride length,

cadence,

and gait speed were not significantly

different from the pre measures, and

the increases that were seen varied

among each individual. The researchers

concluded that strength training may

have the ability to improve walking

function and alignment in some people

with cerebral palsy when weakness is

a big contributor to the deficits in

gait. Furthermore, there may also be

no change or even undesired results

in other patients. A larger sample size

is needed in order to determine validity

of this study.

These findings

contradict the findings of Morton, Brownlee,

& McFadyn (2005),

Eagleton et al. (2004),

Blundell, Shephard, Dean, & Adams

(2003), Nystrom Eek, Tranberg, Zugner,

Alkema, & Beckung (2008)

and Andersson, Grooten, Hellsten, Kaping,

& Mattsson (2003).

In the pilot study by Morton et al.,

eight children with cerebral palsy underwent

a six-week progressive training session,

which included strength training three

times a week.

Measurements

were taken at the beginning, immediately

after, and again after a four-week follow

up. There was a statistically significant

result in the quadriceps and hamstrings

mean strength. As far as the gait results,

self-selected mean walking speed went

from 0.55 m/s to 0.67 m/s post training

and then to 0.62 m/s at the follow-up.

Fast walking speed also increased going

from 0.55 m/s to 0.67 m/s after the

training to 0.62 m/s. Self-selected

cadence increased from 93.96 steps/min

to 108.87 steps/min to 105.64 steps/min.

Fast cadence also increased after the

strength training intervention, and

then decreased following four weeks.

Self-selected step length went from

0.34 m to 0.37 m back down to 0.34 m

at the follow-up. Fast step length also

showed the same changes of an increase

followed by a decrease at the follow-up.

Eagleton et al. examined trunk and lower

body muscle strength as well as gait

velocity, step length, and cadence.

The researchers

recruited seven adolescents with cerebral

palsy to participate in a six-week intervention

of strength training. The findings showed

that all five variables increased significantly.

As a result, the researchers concluded

that resistance raining is an important

form of physical therapy for children

with cerebral palsy.

Blundell et al. (2003)

examined eight children between the

ages of four and eight, with cerebral

palsy, who participated in a training

program that lasted four weeks. The

participants underwent exercises that

were similar to daily tasks in order

to increase functional ability. The

activities included picking up objects

from a couched position to increase

balance, step-ups and step-downs, sit-to-stand

and leg press for strength, and walking

on treadmills, as well as up and down

ramps and stairs. Each session of strength

training was an hour long and two times

a week, with intensity being increased

gradually. After four weeks, not only

were there improvements in muscle strength,

but in functional ability as well. Hip

flexors and extensors, dorsiflexors,

and knee extensors all showed significant

increases in strength and the functional

test in the step-ups, minimum chair

height test, timed walk, and stride

length increased significantly as well.

Eight weeks following the training period,

the improvements were still visible.

Nystrom Eek

et al. (2008)

investigated the influence of strength

training on gait in children with cerebral

palsy. Three days a week for eight weeks,

sixteen children participated in lower

body resistance training including free

weights, rubber bands, and body weight.

At the beginning of training, measurements

were taken in Gross Motor Function

Measure (GMFM)

assessment, joint range of motion assessment,

as well as three-dimensional gait analysis.

After the training period, there were

significant increases in muscle strength

in the knee flexors and hip muscle groups.

There was also a significant increase

in GMFM as well as stride length, but

no significance in gait velocity and

a decrease in cadence after training.

The researchers

concluded that a resistance-training

program increased strength and improved

gait function in children with cerebral

palsy. Andersson et al. (2003)

examined the effects of progressive

strength training on seven individuals

with cerebral palsy, while three were

placed in the control group. After ten

weeks of training twice a week, significant

improvements were seen in isometric

strength (hip extensors p=0.006; hip

abductor p=0.01), isokinetic concentric

work (knee extensors p=0.02). There

were also statistically significant

increases in GMFM (p=0.005) Timed "Up

and Go" test (p=0.01), and walking

velocity (p=0.005). Ross & Engsberg

(2007)

found that spasticity was not related

to gait and motor function, but strength

was highly related to motor function.

Salem &

Godwin (2009)

also went against the findings by Scholtes

et al. (2010),

but along with Blundall et al (2003).

Salem & Godwin examined ten children

with cerebral palsy to assess mobility

after task-oriented strength training.

Five children were assigned to the experimental

group, and five were in the control

group. The children placed in the experimental

group received task-oriented resistance

training focusing on lower body strengthening,

while the children in the control group

focused on improving balance through

reinforcement and normalization of movement

patterns through conventional physical

therapy (Salem

& Godwin). Mobility was measured

using the Gross Motor Function Measure

and the Timed "Up and Go"

test.

After the

five-week session came to an end the

researchers found there were significant

improvements in mobility in the experimental

group. The experimental group significantly

lowered the time to complete the Timed

"Up and Go" test (p=0.017).

Along those same experimental lines,

a study by Andersson et al. (2003)

showed that there were significant improvements

not only in strength, but GMFM and Timed

"Up and Go" test as well.

A similar

study done by Yan, Wang, Lin, Chu, &

Chan (2006)

examined task-oriented progressive resistance

strength and mobility in people with

stroke. Stroke in children often results

in a movement disorder very similar

to that resulting from cerebral palsy

("Cerebral

Palsy," n.d.). The two are

quite similar to each other, making

it important to analyze the studies

done with individuals with stroke as

well. Forty- eight individuals, a year

following a stroke, were either placed

in a control group or the experimental

group. The experimental group underwent

four weeks of task-oriented progressive

strength training while the control

group didn't do any kind of rehabilitation.

After the four weeks, measures were

taken in lower body muscle strength,

cadence, stride, gait velocity, length

of the stride, step test, six-minute

walk test, as well as the Timed "Up

and Go" test.

In the experimental

group, muscle strength significantly

in the strong side, which ranged from

23.9% to 36.5% as well as the paretic

side, ranging from 10.1% to 77.9%. The

control group had changes ranging from

a 6.7% increase to 11.2% decline. In

all of the measures that were examined,

the experimental group showed significant

improvements, while the control group

showed no changes in the measures except

for a significant decline of 20.3% in

the step test. There was a significant

association between the strength gain

and the gain in all the functional tests

in the experimental group. The results

from this study show that task-oriented

strength training may have the potential

to increase lower body strength as well

as functional mobility for people with

stroke, which could translate to people

with cerebral palsy.

Based on

this evidence, the evidence shows that

strength training it may need to be

task-oriented or progressive in nature

in order to see any improvement in mobility

function. Functional training that is

done to mimic everyday tasks, or strength

exercises specific for increasing muscles

used daily, seems to have the best result

according to Blundell et al. (2003)

and Salem & Godwin (2009).

SPASTICITY

There are

many different types of cerebral palsy,

with spastic

cerebral palsy being the most common

(Lehman et al.,

2008). One area of concern for

some physical therapists is the fear

of increasing spasticity because of

the great effort used in strength training.

"The Bobath neurodevelopmental

treatment approach advised against the

use of resistive exercise, as proponents

felt that increased effort would increase

spasticity" (Fowler

et al., p. 1215). Since the development

of that theory there has been advocates

against strength training due to increases

in spasticity despite studies showing

a lack of evidence in increased spasticity

(Scholtes et al.,

2010; Eagleton et al., 2004; Fowler

et al., 2001).

The study

by Andersson et al. (2003)

examined mobility in adults with cerebral

palsy, and spasticity as well. The study

showed that there were significant improvements

in muscle strength without increasing

spasticity. Fowler et al. (2001)

specifically examined whether or not

performance of exercises with maximum

efforts would increase spasticity in

people with cerebral palsy. Twenty-four

participants with cerebral palsy performed

three different forms of quadriceps

femoris exercises (isometric, isotonic,

and isokinetic). Knee spasticity was

measured bilaterally immediately before

and after the exercises using the pendulum

test to obtain a stretch reflex. The

measurements taken by Electrogoniometers

in the Pendulum test included the first

swing excursion, number of lower leg

oscillations, and duration of the oscillations.

The results of the study showed no increase

in quadriceps femoris spasticity after

maximum efforts.

PYSCHOLOGICAL

BENEFITS

In studies,

strength training has not only been

shown to have cardiovascular and neuromuscular-system

advantages, but strength training has

been shown to increase self-image, promote

active lifestyles, as well as encourage

socialization (McBurney,

Taylor, Dodd, & Graham, 2003).

Physical exercise is associated with

increased self-attitudes in people of

all ages who have physical and/or emotional

disorders (Ben-Shlomo

& Short, 1983). Winnick (2005)

states that for people with cerebral

palsy there must be attention paid to

psychological and social development.

A study, looking at the relationship

between quality of life and functional

status of young adults with cerebral

palsy (done by

Tarsuslu & Livanelioglu, 2010)

demonstrated that children with cerebral

palsy were more affected by parameters

related to physical condition, while

psychological and emotional aspects

were more important factors relating

to quality of life for adults with cerebral

palsy.

A study by

Allen, Dodd, Taylor, McBurney, &

Larkin (2004)

examined people with cerebral palsy,

and the positive and negative perceptions

of being involved in a strength-training

program. Ten participants were placed

in a ten-week group resistance-training

program. After the conclusion of the

study, the participants were interviewed

about how well they enjoyed that program.

The results of the interview showed

that the participants felt like his

or her strength had improved, and that

performing everyday tasks was easier,

but the main outcome for the participants

was the enjoyment and the social interaction

the program provided them with.

Negative

perceptions included short-term muscle

soreness, lack of monumental gains in

strength, and fatigue. Enjoyment plays

a vital component of adherence and sustainability

to strength training programs, which

can lead to increased function and socialization

(Allen et al.).

McBurney et al. (2003)

found similar psychological benefits

to strength training.

Contradicting

the studies by Allen et al. (2004)

and McBurney et al. (2003),

Dodd, Taylor, & Graham

(2004) found that an at-home

progressive strength-training program

had an inhibitory effect in regard to

social acceptance in children with cerebral

palsy. Seventeen children with spastic

diplegic cerebral palsy were recruited

to either take part in the strength

training or to be in the control group.

Self-concept measures were taken at

the beginning, right after the training,

and again six weeks after the training

as a follow-up. At baseline, six-weeks,

and at the follow-up, both of the groups

exhibited a positive self-concept. The

experimental group did show a decrease

in self-concept in the area of scholastic

competence and social acceptance after

the training, as well as at the follow-up.

Shields, Loy, Murdoch, Taylor, &

Dodd (2007)

found that children with cerebral palsy

do not have a reduced sense of Global

Self-worth even though they feel less

competent in some aspect of self-concept.

Self-concept may not be lower because

of the diagnosis of cerebral palsy,

but because of some other outside factors

(Shields et al.).

DISCUSSION

After reviewing

the literature concerning people with

cerebral palsy and the effects of strength

training on muscle strength, mobility,

gait function, spasticity, and self-concept,

there seems to be a positive correlation

between "progressive, task-oriented

strength training" in a community

setting and improvements in the dependent

variables. There is also evidence of

the relationship between lower body

strength training and motor functioning,

while there wasn't any evidence of strengthening

exercises increasing spasticity. It

is important that parents as well as

physical educators have an idea of where

weaknesses generally are in children

with cerebral palsy, and what exercises

will work on those areas of concern

(Appendix A.)

Looking into

the future, there should be more research

done in the area of progressive strength

training. One area that hasn't been

researched much is a progressive strength-training

program teamed with a stretching program.

Strength training and stretching are

two of the components of a complete

fitness program. Teaming the two together

may result in different outcomes.

page

2 >>

|